Maury County, Tennessee

| Other Names | "The Dimple of the Universe" |

|---|---|

| Date Founded | 1807 |

| Population | 96,387 (2019 est.) |

| Key Personnel | Andy Ogles (county mayor), Bucky Rowland (sheriff) |

Maury County is a county in the State of Tennessee. It is part of the grand division of Middle Tennessee[1]and a part of the Nashville Metropolitan Area.[2] The county seat is Columbia. The estimated population of Maury County in 2019 was 96,387.[3]

Contents

- 1 Pronunciation

- 2 History

- 3 Geography

- 4 Demographics and Social Statistics

- 5 Government

- 6 Economy and Major Businesses

- 7 Schools

- 8 Health Care

- 9 Arts and Culture

- 10 Transportation

- 11 Communications

- 12 Notable People from Maury County

- 13 References and Footnotes

- 14 External links

- 15 See Also

Pronunciation

Though the Maury family, after whom the county was named, originally pronounced with their surname with an "aw" sound (/ˈmɔːrɪ/)[4], Maury County is generally pronounced as "Murray" (/ˈmʌrɪ/) today.[5][6]

History

Antebellum Period

See main article Maury County before 1800.

See main article Maury County in the Early Nineteenth Century.

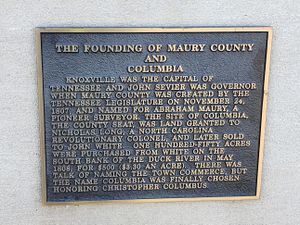

Maury County was established by an act of the Tennessee General Assembly dated November 16, 1807.[2][7][8][9][10] Maury County was created out of parts of Williamson County and the act creating it also instructed its first county commissioners to found the town of Columbia on the Duck River to serve as its seat.[11] Maury County is named after Abram Maury, a planter who served as a state senator from Williamson County and who helped found the town of Franklin, Tennessee.[7][12] Prior to 1806, title to the lands of the Duck River valley were held by the Cherokee Nation; their claims were relinquished by the Third Treaty of Tellico (1805) and the Treaty of Washington (1806).[8][5][13] Giles, Lawrence, and Lewis Counties were later carved out (in part or whole) of Maury County land.[14]

Maury County was relatively prosperous in the early nineteenth century due to its rich soils.[7] Important products included cotton, tobacco and livestock.[7] Maury County was the third-most populous county in Tennessee in 1830[15] and the second most populous (behind only Davidson County) in the 1840 Census.[16][7] Before Nashville was chosen in 1843, locals hoped that Columbia (which is near the geographical center of the state) might become the state capital.[17][18]

The early history of Maury County is closely tied to the Polk family.[7] The petition to form Maury County was signed by several members of that family, including Samuel Polk,[19] the father of President James K. Polk.[20] Several historic properties including the James K. Polk House (built 1816) on West 7th Street in Columbia are associated with the Polk family.[21]

The labor of enslaved African-Americans was a key ingredient to the county's early success.[2] By the eve of the Civil War, there were nearly as many enslaved people in Maury County as free citizens.[22] Hundreds of families claimed ownership of other human beings. While many owned only one or a small number, several families (including the Polk family[23]) held dozens or hundreds of people in bondage[24][25]. Several prominent families, such as the Cheairs family of Rippavilla Plantation, built large estates during the antebellum period by exploiting the labor of the enslaved[26][27] During the 1820s and 1830s some citizens spoke out against the practice of slavery on moral and religious grounds, founding the Manumission Society of West Tennessee in Maury County in 1824; but their efforts at persuading their neighbors to free their slaves were largely unsuccessful.[28] Furthermore, many freed slaves left Tennessee either by choice or under legal banishment.[29]

| Free White (% of Total) | Slaves (% of Total) | Free Colored Persons (% of Total)[30] | Other (% of Total) | Total (% Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1810[31] | 7,722 (74.5%) | 2,626 (25.3%) | 11 (0.1%) | n/a | 10,359 (n/a) |

| 1820[32] | 15,620 (70.5%) | 6,420 (29.0%) | 49 (0.2%) | 52 (0.2%) | 22,141 (+113.7%) |

| 1830[15][31] | 18,200 (65.8%) | 9,434 (34.1%) | 31 (0.1%) | n/a | 27,665 (+24.9%) |

| 1840[16] | 17,090 (60.6%) | 11,002 (39.0%) | 94 (0.3%) | n/a | 28,186 (+1.9%) |

| 1850[33] | 16,759 (56.8%) | 12,670 (42.9%) | 91 (0.3%) | n/a | 29,520 (+4.7%) |

| 1860[22] | 17,701 (54.5%) | 14,654 (45.1%) | 143 (0.4%) | n/a | 32,498 (+10.1%) |

Civil War

See article Maury County in the Civil War.

Voters in Maury County overwhelmingly (2,731 for, 58 against) supported secession in the June 1861 Tennessee state referendum, and at least 21 companies of Confederate infantry and cavalry were organized in Maury County.[34]

Maury County was occupied by the Union (U.S.) Army during the summer of 1862 after the capture of Nashville, but abandoned in the fall of that year[35] Both Union and Confederate units passed through Maury County during the fall of 1864; Confederate General John Bell Hood sent his Army of Tennessee northward in a bid to capture Nashville during the Franklin-Nashville campaign. This movement, as well as the Union Army rushing to combine forces scattered across Middle Tennessee, resulted in minor skirmishes at Columbia on November 24, Davis Ford (near Fountain Heights) on November 28, Hurt's Crossroads on November 29, and the Battle of Spring Hill (the only major battle of the Civil War to be fought in Maury County) on November 29, 1864.[36] After the decisive Union victory at Nashville in early December 1864, retreating Confederate units commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest briefly held Columbia before abandoning Maury County to advancing Union troops during the week of Christmas 1864.[37]

A number of buildings, including Jackson College in Columbia, were burned during the Civil War.[38]

Confederate General Earl Van Dorn was shot dead by Dr. George Peters at the home of Matt Cheairs in Spring Hill on May 7, 1863; Dr. Peters believed Gen. Van Dorn was having an affair with his wife.[39]

Maury County was the home of Private Sam Watkins, whose book Company Aytch, or a Side Show of the Big Show: A Memoir of the Civil War has become a well-known primary source on the Civil War in Tennessee.[40]

Post-Civil War Years

In 1865 and 1866, the State Tennessee abolished slavery by statewide referendum, disenfranchised Confederates, and set about on a course of Radical Reconstruction under the leadership of Governor William G. "Parson" Brownlow.[41][42][43] Many white Maury County residents, outraged over these changes, participated in the violent activities of the first Ku Klux Klan (which was founded in neighboring Giles County in 1865 or 1866), terrorizing freed African-Americans as well as white Republicans.[44][45] By the 1870s, former Confederates had been restored and were a key part of the power structure in Tennessee politics for the rest of the century.[46]

From 1865 until 1872, the Freedmen's Bureau opened schools in Columbia, Culleoka, Mount Pleasant, and Spring Hill to educate the newly-freed African Americans of Maury County.[47]

At the end of the nineteenth century, Maury County remained among the top Tennessee counties in terms of wealth, population, and agricultural output. Columbia had the third-largest mule market in the United States.[48]

In 1888, William Shirley, digging around Gholston Hill in what is today Columbia, discovered brown phosphate rock which had significant value for the manufacturing of fertilizer.[49][50]Phosphate was also discovered in Mount Pleasant in 1896, which turned Mt. Pleasant into a boomtown.[51][52] Exploitation of this mineral resource began during the last decade of the nineteenth century and over the following decades helped to transform Maury County into an important industrial area.[53][54]

| White (% of Total) | Non-White (% of Total) | Total (% Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870[31] | 20,022 (55.2%) | 16,267 (44.9%)[55] | 36,289 (+11.7%) |

| 1880[56] | 21,731 (54.5%) | 18,173 (45.5%)[57] | 39,904 (+10.0%) |

| 1890[58] | 22,201 (58.3%) | 15,911 (41.7%)[59] | 38,112 (-4.5%) |

| 1900[60] | 24,539 (57.5%) | 18,164 (42.5%)[61] | 42,703 (+12.0%) |

In 1900, the population of Columbia had grown to 6,052 and the population of Mt. Pleasant was 2,007.[60]

Twentieth Century

Migration, Urbanization, and Rural Decline

The population of Maury County shrank during the first half of the twentieth century due to two related migrations. First, many people, particularly African-Americans, left Maury County during this time period (and indeed, many African-Americans had already left Tennessee after the Civil War due to racial violence[62]) as part of the Great Migration from the rural South to urban areas, particularly to cities in the North.[63][64] Second, the population of rural districts in Maury County declined while the urban population (particularly in Columbia) grew.

| White (% of Total) | Non-White (% of Total) | Urban (% of Total) | Rural (% of Total) | Total (% Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910[65] | 24,287 (60.0%) | 16,169 (40.0%)[66] | 5,754 (14.2%)[67] | 34,702 (85.8%) | 40,456 (-5.3%) |

| 1920[68] | 23,453 (66.2%)[69] | 11,950 (33.8%)[70] | 5,526 (15.6%) | 29,877 (84.4%) | 35,403 (-12.5%) |

| 1930[71] | 24,208 (71.2%)[72] | 9,808 (28.8%)[73] | 7,882 (23.2%) | 26,134 (76.8%) | 34,016 (-3.9%) |

| 1940[74] | 30,225 (74.9%)[75] | 10,130 (25.1%)[76] | 13,668 (33.9%)[77] | 26,689 (66.1%)[78] | 40,357 (+18.6%) |

| 1950[79] | 31,782 (78.7%) | 8,586 (21.3%)[80] | 13,842 (32.8%)[81] | 26,526 (67.2%)[82] | 43,376 (+0.0%) |

| 1960[83] | 33,314 (79.9%) | 8,385 (20.1%)[84] | 20,545 (49.3%)[85] | 21,154 (50.7%) | 41,699 (+3.3%) |

| 1970[86] | 35,307 (81.4%) | 8,069 (18.6%)[87] | 25,001 (57.6%)[88] | 18,375 (42.4%) | 43,376 (+4.0%) |

These trends were both cause and effect of a decline in the importance of agriculture in Maury County. By 1940, agricultural workers made up a minority of the County's workforce[74] and by 1950 a majority of the rural population no longer lived on a farm.[79]. During the mid-twentieth century, farms increasingly were operated by owners (rather than by sharecroppers, which had been a major source of farm labor in years past) and many farms began using machinery to increase productivity.[89]

The relative importance of Maury County in Tennessee also declined during this time. By mid-century, Maury County was no longer in the top ten counties by population, falling behind thirteen other counties (Shelby, Davidson, Knox, Hamilton, Sullivan, Madison, Washington, Anderson, Blount, Gibson, Montgomery, Carter, and Rutherford).[79]

The First Industrial Boom (and Bust): Columbia and Mount Pleasant

The phosphate boom of the late nineteenth century continued into the early decades of the twentieth, particularly in Mt. Pleasant. By 1904, Mt. Pleasant leaders felt their town was influential enough to try to get the county seat moved there from Columbia (ultimately, the current county courthouse was built in Columbia).[90]

Advances in mining and process techniques, as well as the establishment of fertilizer plants and elemental phosphorous furnaces in Maury County, helped the phosphate boom continue through the first half of the twentieth century, A major employer was Monsanto, which pronounced elemental phosphorous as well as high-quality steel using complex and often-dangerous (both to the workers and to the environment) methods in a sprawling 3,500-acre complex west of Columbia.[91] Increased operational costs, falling market demand, and depletion of mineral reserves in the county led to a decline in the manufacturing sector during the second half of the century, with major facilities closing in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.[92]

In 1962, near the peak of Maury County's first industrial boom, Maury County posted a full-page advertisement in The Tennessean touting the county's progress. At the time, five of the top 50 largest industrial companies in America had plants in Maury County, with 45 total industrial plants in the county. The advertisement claimed industrial payroll of 5,000 employees with $25,000,000 in annual payroll; 40 percent of this (by payroll) was attributed to the phosphate industry, with the other 60 percent coming from the production of items ranging from carbon electrodes, nylon hosiery, cellulose sponges, stock feed, aluminum tubing, furniture, soft drinks, and children's clothes. The advertisement stated that Maury County was eighth out of Tennessee's 95 counties in industrial payrolls and emphasized that local political leadership "understand industrial relations... and appreciate the economic and community contribution of our good industrial citizens, large and small."[93]

| Top Industry (Workers) (% of Total) | Second Industry (Workers) (% of Total) | Third Industry (% of Total) | Total Workforce[94] (% Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940[74] | Agriculture (4,797) (31.1%) | Domestic Service (1,397) (9.1%) | Chemicals (1,363) (8.9%) | 15,400 (n/a) [95] |

| 1950[79] | Agriculture (4,014) (26.8%) | Manufacturing (2,853) (19.0%)[96] | Other Retail Trades (1,079) (7.2%)[97] | 14,996 (-2.6%) [98] |

| 1960[83] | Manufacturing (4,030) (25.7%))[99] | Agriculture (2,241) (14.3%) | Other Retail Trades (1,326) (8.4%)[100] | 15,652 (+4.3%)[101] |

Columbia Race Riot of 1946

See main article Columbia Race Riot of 1946.

Lynchings - the killing of often-innocent people by armed vigilantes, usually as a means to assert white racial supremacy - were an unfortunately common phenomenon in the Southern United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with more than 214 lynchings in Tennessee between 1882 and 1930.[102] Maury County gained national notoriety for the lynchings of two young African-American men, both accused (with little or no evidence) of having attacked young white women, in 1927 and again in 1933.[103]

On February 25, 1946, a disagreement over a radio repair led to a street brawl outside of a Columbia department store between black customers and a white radio repairman.[104][105][106] A mob of angry white citizens formed in downtown Columbia, and some of the town's black citizens took up arms to defend the black-owned businesses there.[107][108][109] The tense situation escalated when four Columbia police officers were fired upon and wounded by a crowd of black men.[110][111]

During the early morning hours of February 26, the Tennessee Highway Patrol entered into the black-owned business area, ransacking and vandalizing buildings and arresting (and often beating) dozens of people[112][113]. By February 28, over 100 black citizens had been arrested and held without bail or legal representation for days.[114] Two black men were killed by state troopers after the prisoners grabbed confiscated guns that were being stored in the jail.[115][116].

Lawyers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) intervened following the mass arrests on February 26-28, obtaining acquittals for 26 out of 27 black defendants tried during the summer and fall of 1946.[117]

County Jail Fire of 1977

See main article Maury County Jail Fire of 1977.

Forty-two people (33 inmates and 9 visitors) died on June 26, 1977, from smoke inhalation after a fire broke out at the Maury County Jail in Columbia. The fire was started by a troubled runaway teenager who was being held in a padded room lined with synthetic padding. This event was one of the most-deadly structure fires in Tennessee and the second-worst jail fire in American history.[118][119][120]

The Second Boom: Spring Hill Becomes A Different Kind of Community

Maury County's population began to grow significantly in the 1970s, a part of a regional trend of young families choosing to stay in Middle Tennessee rather than leaving the area.[121] But, other counties nearby -- particularly Williamson County -- grew even more rapidly as they began to develop strong suburban cultures, and "white flight" drove some families out of Nashville, leaving Maury County a relative backwater in the Nashville metropolitan area.[122] In 1981, the phosphate industry still formed the industrial base of Maury County -- a base that was in decline.[123][124]

In the early 1980s, American automobile manufacturers lost market-share to Japanese carmakers, who earned a reputation for reliable quality.[125] In 1983, Nissan opened a manufacturing plant to build small trucks in Smyrna, in Rutherford County, Tennessee.[126] In January 1985, General Motors announced that it was launching a new division, Saturn, to produce a new line of small cars to compete with Japanese imports.[127] States and towns across the country lobbied GM for its new manufacturing plant, with early rumors suggesting that a site in the Midwest would be selected.[128]

Meanwhile, General Motors was negotiating with the United Auto Workers on a new collective-bargaining agreement. On July 26, the UAW and General Motors agreed to their new contract,[129] and rumors were confirmed that GM had selected Spring Hill, Tennessee as the site for its new Saturn plant.[130]. The first Saturn automobiles rolled off the assembly line in July 1990 and were sent to dealers in October.[131][132]

At the time of the General Motors announcement, Spring Hill had a population of only 1,095.[133] The site selected for the plant had long been part of the Haynes Haven horse farm.[134] The Saturn plant employed 3,350 people by 1990.[135] Spring Hill's population grew to 1,464 by 1990 (a 48 percent increase over 1980) and 7,115 by 2000 (a 479 percent increase over 1990). The rapid growth of Spring Hill and surrounding areas brought growing pains; school overcrowding strained teachers, and some children of GM workers relocated from Michigan found it difficult to adjust to Maury County's traditional Southern culture.[136] Real estate prices soared, while crime and traffic became regular occurrences in the formerly-sleepy community of Spring Hill, even after major infrastructure improvements such as Saturn Parkway (Tennessee Highway 396) were constructed.[137][138] Some Maury County natives, many left unemployed after phosphate and apparel jobs disappeared, were disappointed by General Motors' practice of employing relocated UAW workers instead of struggling Tennesseans.[139]

Saturn sales peaked in the mid-1990s, and by the end of the millennium, the Saturn line was struggling.[140][141] Major layoffs occurred in 2005, and the plant (now GM Spring Hill Manufacturing) was re-tooled for other GM products and today is the company's largest facility.[142][143] Saturn employment peaked at around 5,700.[144]

Twenty-first Century

Suburbanization and Commuter Communities

In the closing years of the twentieth century and opening decades of the twenty-first century, Maury County became more tightly integrated with the Nashville metropolitan area. Commuting from Columbia to Nashville became a common phenomenon in the 1990s.[145] Spring Hill, in particular, has developed a "commuter community" culture.[146] At the same time, there was a movement away from the downtown areas of Columbia and Mount Pleasant toward suburbs and rural areas.[147]

| Urban (% of Total) | Rural (% of Total) | Total (% Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 29,747 (58.2%)[148][149] | 21,348 (41.8%)[148] | 51,095 (+17.8%)[148] |

| 1990 | 32,422 (59.2%)[150][151] | 22,390 (40.8%)[150][152] | 54,812 (+7.3%)[150] |

| 2000 | 39,363 (56.6%)[153][154] | 30,135 (43.4%)[153] | 69,498 (+26.8%)[153] |

| 2010 | 47,284 (58.4%)[155][156] | 33,672 (41.6%)[155] | 80.956 (+16.5%)[155] |

Historiography

See article Historical Markers and Monuments in Maury County.

See article Historic Preservation in Maury County.

Traditionally, historical production and memorialization in Maury County have tended to exclude racial minorities and promote historical narratives (such as the "Lost Cause" narrative with regard to the memory of the Civil War) that spotlighted affluent white citizens of the county. In recent decades, however, writers and archivists have become more inclusive, in part due to the work of groups such as the African-American Heritage Society of Maury County.[157]

Geography

Location

The Maury County Courthouse is located at 35° 36' 54" North, 87° 2' 2" West. It is located 40.5 miles (65.2 kilometers) south-southwest (200°) of the Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville, Tennessee and 595.6 miles (958.5 km) west-southwest (248°) of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.[158] It is in the Central Time Zone (UTC -6 or -5 during Daylight Saving Time).[159]

Area

Maury County contains 613.1 square miles (1,588 square km) of land area and 2.4 square miles (6.3 square km) of water.[160]

Coding

The FIPS (Federal Information Processing System) code for Maury County is 47119.[161]

Human Geography

Communities and Areas of Maury County

These are unincorporated areas unless specified. For neighborhoods of a particular city, see the entry for that particular city.

- Ashwood

- Athendale

- Bigbyville

- Campbell's Station

- Columbia (city)

- Cross Bridges

- Culleoka

- Fly

- Fountain Heights

- Glendale

- Hampshire

- Hollywood

- Lasea (partly inside the city limits of Columbia).

- Mount Joy

- McCain's

- Mount Pleasant (city)

- Neapolis (partly inside the city limits of Columbia).

- Poplar Top

- Rally Hill

- Santa Fe

- Sandy Hook

- Sawdust

- Southport

- Spring Hill (city, partly in Williamson County)

- Summertown (part, mostly in other counties)

- Theta

- Tice Town

- Williamsport

- Zion

Historical Communities and Areas in Maury County

This is a list of places appearing on old maps that are no longer in widespread use.[163]

- Allensville - according to D.P. Robbins[164] this community was located on Big Bigby Creek about two miles west of Mount Pleasant.

- Bristow - an old Post Office was located here on the old Santa Fe Pike near Knob Creek; today called Athendale.

- Broadview - Robbins[165] describes this a hamlet 10 miles south of Columbia on the Campbellsville Pike; just south of Bigbyville.

- Bryant's Station - an area just east of Park's Station, also on the railroad to Lewisburg, just east of the present-day intersection of Tennessee Highway 50 and Interstate 65 in southeast Maury County, near the Marshall County line.

- Carter's Creek Station - an old railway station was located here between Columbia and Spring Hill in an area that would now be described as part of Neapolis. [166]

- Cedar Spring - mentioned in the 1834 Tennessee Gazetteer as having a post office.

- Dark's Mill - a Post Office was located here near where Rutherford Creek and Carter's Creek join, between Neapolis and Columbia. There is still a Dark's Mill Road in this general area.[167]

- Enterprise - an area located here southeast of Mt. Pleasant; Route 166 is still called "Enterprise Road" and there is an Enterprise United Methodist Church.

- Ewell's Station - a railroad depot existed just northwest of Spring Hill near the Williamson County line.

- Fike's Mill - noted by Bob Duncan as being across the Duck River from Williamsport.[168]

- Glenn's Store - a Post Office was located in this area in the extreme northeastern part of Maury County near Little Flat Creek.

- Godwin - also called Duck River Station; an area just northwest of Columbia near where Highway 7 crosses the Duck River. [169]

- Gravel Hill - Near Theta.

- Groveland - According to Robbins[170], this community was located about 7.5 miles southeast of Columbia on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad branch. Now Fountain Heights.

- Hardison's Mill - an area on the extreme eastern margin of Maury County near where U.S. Highway 431 crosses the Duck River.

- Hurricane Switch - an area just west of Fountain Heights, now called Glendale.

- Hurt's Crossroads - an area in the extreme northeastern part of Maury County near Little Flat Creek.

- Isbell - mentioned by Bob Duncan as being at the end of Polk Lane; near the Maury County Regional Airport east of Mount Pleasant.[171]

- Isom's Store - a Post Office was located here, about two miles north of Hampshire.

- Kedron - absorbed by Spring Hill.

- Kinderhook - an area near Fly, close to the intersection of Highway 7 and the Natchez Trace Parkway.

- Kleburne - site of a large dairy farm, north of Neapolis and South of Spring Hill, near the current location of the General Motors Spring Hill Manufacturing complex. Now part of Spring Hill.

- Lee's Corner - in northeast Maury County.

- Lick Skillet - according to Bob Duncan, east of Howard's Bridge; this would put it near where Interstate 65 crosses the Duck River today.[172]

- Mooresville - mentioned in 1834 Tennessee Gazetteer as being the location of a post office 15 miles southeast of Columbia. Now in Marshall County.

- Orr's Crossroads - an area on the extreme eastern edge of Maury County near the intersection of modern-day U.S. Highway 431 and Tennessee Highway 99.

- Park's Station - an area east of Culleoka just west of the present intersection of Highway 50 and Interstate 65.

- Pottsville - an area near the intersection of State Highway 99 and U.S. 431 north of the Duck River near the Marshall County line.

- Pleasant Grove - According to Bob Duncan, "[m]ight as well be Culleoka." [173]

- Ridley - appears on a 1905 Map of Maury County, just north of Mt. Pleasant.

- Scott's Mill - also known historically as Ettaton and New York, was located in the southeastern part of Maury County.[174]

- Screamer - mentioned by Bob Duncan as being south of Enterprise.[175]

- Stiversville - mentioned by D.P. Robbins. Southwest of Culleoka.

- Water Valley - an area west of Santa Fe.

- Woodlawn Mills - an area immediately west of Spring Hill,

Physical Geography

Landforms

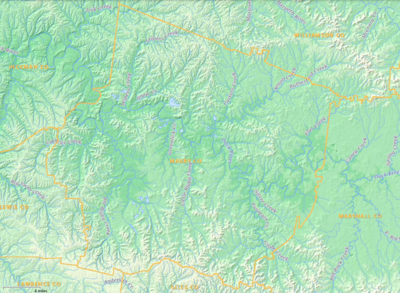

Maury County is located on the southwestern edge of the Nashville Basin (also known as the Central Basin). The Nashville Basin is a relatively low area in Middle Tennessee bounded by the Eastern Highland Rim on its east (beyond which lies the Cumberland Plateau), and the Western Highland Rim on its west (beyond which lies the valley of the Tennessee River).[176][177][178]

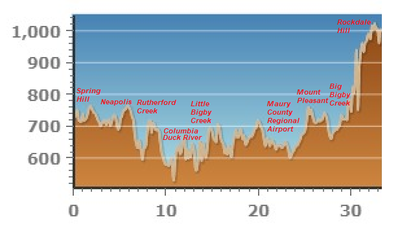

The most notable physical features are the valleys of the Duck River and its main tributaries (particularly Big Bigby Creek and Rutherford Creek). The floodplains of the Duck River and its tributaries are relatively low (less than 700 feet, or 210 meters above sea level) with flat ground or gently rolling hills. Outside of these valleys, near the northwest, west, and southern county lines, the elevation and relief increase significantly. Just beyond the southern border of Maury County, in Giles County, lies Elk Ridge, which separates the Duck and Elk River drainage basins. North of the Maury County line in southern Williamson County is a ridge that separates the Tennessee (Duck) River basin from the Cumberland (Harpeth) River basin.[179]

The tallest points include Flanigan Hill at 1,152 feet (351 meters) in southern Maury County; Kansas Hill at 1,089 feet (332 meters) in southern Maury County; Toombs Hill, in southeastern Maury County near Culleoka, also at 1,089 feet; Watts Hill at 1,043 feet (318 meters) south of Mount Pleasant; and Rockdale Hill at 1,030 feet (314 meters) between Mount Pleasant and Summertown.[180]

Waters and Streams

See also the article Floods in Maury County.

Almost all of Maury County is in the Duck River watershed, with the majority being considered to be in the Lower Duck River watershed and the eastern quarter of the county (east of Columbia) in the Upper Duck watershed.[181][182]A very small part of Maury County along the Giles County border near Enterprise is in the Lower Elk River watershed.[183][184] Both the Duck and Elk are tributaries of the Tennessee River, which flows into the Ohio River. The Ohio River, in turn, flows into the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico.[185]

The Duck River flows for about 75 miles in Maury County.[186] The level of the Duck River in Maury County is affected both by releases from the upstream Normandy Dam as well as groundwater discharges from local aquifers.[187] The river is the source for most of the water used by residents of Maury County, and can be strained during drought conditions.[188]

The power of flowing water has been harnessed by mills built along the Duck and its tributaries since about 1820.[189] In the mid-nineteenth century, a scheme was established to make the Duck River fully-navigable, and two dams were built; but due to poor engineering, very few boats were ever able to make it to Columbia, and then only at high water.[190] A low-head dam on the Duck River in Columbia, first constructed in the 1920s, still stands but no longer generates electric power.[191]

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Tennessee Valley Authority (which operates the Normandy Dam in Coffee County[192]) planned for and nearly completed construction of a massive hydroelectric dam east of Columbia, but the TVA Columbia Dam project was canceled due to concern over whether the cost to complete the dam justified its benefits; local activists also raised environmental concerns, particularly with regard to the impact the dam would have on endangered species of freshwater mussels in the Duck River.[193][194] The land acquired by the TVA for the proposed reservoir was donated to the State of Tennessee in 2001 for public use.[195]

Major streams flowing into the Duck River in Maury County include (from upstream to downstream):

- Flat Creek (right tributary).

- Fountain Creek (left tributary) including its branch, Silver Creek.

- Bear Creek (right tributary), which joins the Duck near Columbia.

- Lytle Creek (left tributary), which joins the Duck near Columbia.

- Rutherford Creek (right tributary) including its branches Carter's Creek, McCutcheon Creek, and Aenon Creek, which joins the Duck near Columbia.

- Little Bigby Creek (left tributary) which joins the Duck west of Columbia.

- Knob Creek (right tributary) which joins the Duck near Athendale.

- Greenlick Creek (left tributary) which joins the Duck west of Athendale.

- Snow Creek (right tributary) which joins the Duck near Williamsport.

- Leiper's Creek (right tributary) which joins the Duck near Williamsport.

- Poplar Creek (left tributary) which joins the Duck near Williamsport.

- Big Bigby Creek (left tributary) which joins the Duck west of Williamsport.

- Cathey's Creek (left tributary) which joins the Duck near the Hickman County line.

In addition to the Duck River and groundwater, there are a number of ponds in Maury County, many of which were created artificially.[196]

Geology and Soils

Maury County sits at the southwestern end of the Central (Nashville) Basin. Structurally, the Central Basin is an anticline, with rock layers dipping gently away from its center (in Maury County, this means that rock layers dip toward the southwest). Differential erosion of an ancient uplift (the Nashville Dome) results in older surface rocks near the middle part of the Central Basin. As one approaches the Highland Rim (i.e. the western parts of Maury County), surface rocks become progressively younger.[197]

The rocks themselves were laid down over a period of hundreds of millions of years when Tennessee was covered by shallow seas, lagoons, and beaches. Limestone - a dominant type of rock in Maury County - was created by the compression of the shells of ancient marine creatures. The Nashville Dome began to be uplifted about 450 million years ago (mya) with most of the uplift occurring at the time of the Alleghanian orogeny (when the Cumberland Plateau and Smoky Mountains of East Tennessee were formed by the collision of ancient North America with ancient Africa) about 300 mya, during the late Paleozoic Era. Since that time, erosion has cut into the Dome, removing over a mile of rock.[198]

Most of the exposed surface rocks and near-surface bedrock in Maury County are sedimentary rocks of Paleozoic age. The oldest rocks are the Ordovician (485-444 mya) limestones of the Stones River Group, which dominate the areas east of Interstate 65 as well as the lower-lying areas of the Duck River valley. At somewhat higher elevations, and in most of the county west of Interstate 65, are the younger Ordovician limestones and sandstones of the Nashville Group, which includes the phosphate-rich Bigby-Cannon Limestone, and the Leipers-Cathey Group limestones above that. At the highest elevations, particularly in the western part of the county, Silurian (Wayne Group, laid down approximately 430 mya) and Mississippian (Fort Payne Formation, laid down approximately 350 mya) limestones and shales dominate.[199]

The geology of Maury County has been economically important. The phosphate-rich Bigby-Cannon formation (formed from the shells of sea creatures who pulled phosphorous out of the ancient seawater) gave rise to the phosphate industry here. The sedimentary rock layers of Maury County led to the formation of aquifers and caves.[200][201]

Due to the origin and age of Maury County's rocks, most of the fossils found here are from marine invertebrates (such as mollusks) from the mid-to-late Paleozoic Era. A few fossils of Pleistocene ("Ice Age") age -- such as bones from mastodons (Mammuthus sp.), giant sloths (Megalonyx), and turtles -- have also been found in phosphate pits and caves.[202][203][204]

The soils of Maury County vary primarily the result of weathering and erosion of local parent rocks, though in some areas (such as the Duck River bottoms) alluvial soils dominate. The soils of the western part of the county tend to be more cherty than the soils of the central and eastern parts of the county, which are more clayey and high in phosphorous. Most of the soils of Maury County (except for some alluvial soils) tend to have good drainage, low amounts of lime and other bases, and only a moderate amount of organic material due to the warm, humid climate. Leaching of the soil has also helped to concentrate phosphates.[205][206]

Flora and Fauna

Maury County is located in the Outer Central (Nashville) Basin and Western Highland Rim level 4 ecoregions, both part of the Interior Plateau level 3 ecoregion. These ecoregions are both dominated by oak-hickory deciduous forests and pastures. Much of the original forest has been cleared in the past two centuries.[207]

Maury County frequently ranks high among Tennessee counties for deer hunting, ranking 7th out of 95 counties in Tennessee for total number of deer harvested between January 1, 2011 and January 1, 2021 (with 35,043 deer taken during that ten-year period). The county also ranked highest in the state for total number of wild turkeys harvested during the same time period (with a harvest of 11,600 turkeys).[208]

The Duck River is one of the most biodiverse rivers in the United States and is the home, particularly for fish and freshwater mussels. Several species that make the Duck River their home cannot be found anywhere else on Earth.[209]

The following species of plants found in Maury County have been considered endangered (either on state or federal lists):

- Price's potato bean (Apios priceana).

- Velvety cerastium (Cerastium arvense var. velutinium).

- Leafy prairie-clover (Dalea foliosa).

- Short's Bladderpod (Lesquerella globosa).

- Sand Grape (Vitis rupuestris).[210][211]

The following endangered species of river mussels may also be found in Maury County:

- Duck River dartersnapper (Epioblasma ahistedti).

- Birdwing pearlymussel (Conradilla caelata or Lemiox rimosus).

- Cumberlandian combshell (Epioblasma brevidens).

- Oyster mussel (Epioblasma capsaeformis).[212]

- Tan riffleshell (Epioblasma florentina walkeri).

- Cracking pearlymussel (Hemistena lata).

- Orange-foot pimpleback (Plethobasus cooperianus).

- Cumberland monkeyface (Quadrula intermedia).

- Pale lilliput (Toxolasma cylindrellus).

- Slabside pearlymussel (Pleuronaia dolabelloides).

- Snuffbox (Epioblasma triquetra).

The only vertebrate animals to be listed as endangered by the federal government in Maury County are the Hellbender the Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis) and the Gray Bat (Myotis grisescens). Two species of salamanders are considered threatened or endangered at the state level: the Hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis and the Tennessee Cave Salamander, Gyrinophilus palleucus. Three species of fish -- the Saddled madtom (Notorus faciatus), the Coppercheek darter (Etheostoma aqauli), and the Striated darter (Etheostoma striatulum) -- are listed as threatened at the state level.[213]

Climate

See also the article Tornadoes in Maury County.

As with most of Tennessee, Maury County has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen type Cfa).

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Temperature (°F/°C) | 48.5 9.2 |

53.3 11.8 |

62.2 16.8 |

72.0 22.2 |

79.1 26.2 |

86.1 30.1 |

89.2 31.8 |

88.7 31.5 |

83.2 28.4 |

72.6 22.6 |

60.7 15.9 |

51.5 10.8 |

| Minimum Temperature (°F/°C) | 28.4 -2.0 |

31.4 -0.3 |

37.9 3.3 |

45.5 7.5 |

54.9 12.7 |

63.3 17.4 |

67.1 19.5 |

65.1 18.4 |

58.2 14.6 |

46.4 8.0 |

36.2 2.3 |

31.0 -0.6 |

| Precipitation (inches/mm) | 4.69 119 |

4.97 126 |

5.37 136 |

5.07 129 |

4.98 126 |

4.69 119 |

4.47 114 |

3.78 96 |

4.12 105 |

3.82 97 |

3.93 100 |

5.48 139 |

The average precipitation for years between 1991 and 2020 was 55.4 inches (140.7 cm).[215] Between 1895 and 2021, the five wettest years (calendar years from January to December) were 1941 (34.3"), 2007 (36.6"), 1931 (39.4"), 1901 (39.5"), and 1901 (39.9").[216]

Maury County is in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7a, with an average minimum temperature of 0° to 5°F based on data from 1976-2005.[217] According to The Old Farmer's Almanac website (using 1981-2010 climate data for Columbia), the last spring frost is expected by April 21 and the first fall frost is expected after October 20, for a growing season of 181 days.[218]

Severe weather tends to peak in the spring months. Maury County is part of the area of the south-central United States prone to tornadoes between February and May known as "Dixie Alley."[219]

Environmental Quality

Maury County has struggled with air pollution issues in the past, but today the air quality has improved.[220]

There are several brownfield (former industrial) sites in Maury County that are being rehabilitated. None of them are currently on the Superfund National Priorities List, due to their relatively modest environmental impact. These sites are being cleaned by either the state of Tennessee or by the responsible parties (e.g. former and current property owners).[221]

The non-NPL sites are:

- the Monsanto site west of Columbia.

- the Stauffer Chemical Company furnace site on Mount Joy Road in Mount Pleasant.

- the Stauffer Chemical Company organic plant on Mount Joy Road in Mount Pleasant.

- the Industrial Products site on Boswell Street in Mount Pleasant.

- the Cowley Container site on South Park Drive in Mount Pleasant.

- the Rhone Poulenc site on Arrow Mines Road in Mount Pleasant.

Maintaining the quantity and quality of water in the Duck River has been a long-term challenge.[222]

The county government has also been challenged with finding suitable landfill locations for dumping the county's solid waste.[223]

Demographics and Social Statistics

Population Growth and Distribution

The Census Bureau estimated the population of Maury County in July 2019 as 96,387, an increase of 19.1% from the April 2010 Census.[3] The results of the 2020 Census should be released in the Summer of 2021.[224]

Maury County was the 16th-largest county in Tennesee by population and the sixth-fastest growing county by percent change (2010-2019). The county is growing slower than some of its neighbors however (Trousdale, Williamson, Wilson, Rutherford, and Montgomery counties all grew faster. Maury County's population growth may allow it to pass Madison County and Sevier County (which have similar populations but much slower growth rates) to move up to the 14th spot in the 2020 Census.[225]

The population density in 2019 was approximately 157 people per square mile (about 60 people per square kilometer). This was slightly below the statewide average population density of approximately 166 people per square mile in 2019.[226]

About 58 percent of people in Maury County live in an urban area, based on the 2010 Census.[155]. The largest city entirely within Maury County is Columbia with a 2019 estimated population of 40,335.[227] Spring Hill has a larger population (estimated by the Census Bureau at 43,769 in 2019) but the majority of Spring Hillians live in Williamson County; a 2018 special municipal census found 11,442 Spring Hill residents in Maury County and 28,994 in Williamson County.[228][229]

There were an estimated 34,688 households in Maury County in 2019.[3]

Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity

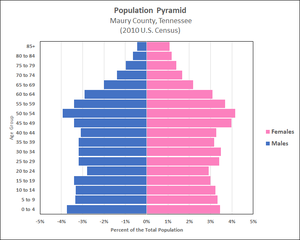

In 2010, the median age in Maury County was 38.4, with a median age for males of 36.9 and a median age for females of 39.8. The Census Bureau estimated that the median age had increased to 39 in 2019 (37.7 for males and 40.1 for females).[230]

The Census Bureau estimated in 2019 that 23.3 percent of the county's population (22,433) was under the age of 18; this is a decrease as a relative share of the population from 2010 (24.3 percent) but an increase in absolute numbers (+2,776, or +14.1 percent). Meanwhile, the over-65 share of the population was 16.3 percent in 2019, up from 12.9 percent in 2010. The over-65 population grew 50.2 percent in absolute numbers between 2010 and 2019.[230][3] The over-65 share of the population is however somewhat lower in Maury County than in the state of Tennessee as a whole (16.7 percent).[226]

For the whole population, 51.7 percent of Maury County residents (based on 2019 estimates) are female. However, the ratio of males to females varies significantly across age groups; there are about 102 males for every 100 females from birth to age 24; about 95 males for every 100 females from age 25 to 44; about 92 males per 100 females from 45 to 64; and about 81 males per 100 females over the age of 65.[230]

In 2019, about 84.1 percent of Maury County residents were white alone; 12.0 percent were black/African-American alone; 1.0 percent were Asian-Americans alone; 0.5 percent were Native American alone; 2.4 percent were bi- or multi-racial. About 6.2 percent identified as Hispanic or Latino; 78.7 percent were white and not Hispanic or Latino.[3] Columbia had a population that was 68.4% white non-Hispanic in 2019 (with black or African-American residents making up 18.5 percent of the city's population), and Spring Hill had a population that was 85.4 percent white non-Hispanic.[227][228]

The Census Bureau estimated that about 3.5 percent of Maury County residents were foreign-born. About 5.5 percent speak a language other than English in the home.[3]

Wealth and Income

The Census Bureau estimated that median household income in Maury County was $57,170, somewhat higher than the statewide median of $53,320. But, the Bureau also estimated per-capita income to be slightly lower than the statewide per-capita income ($28,970 per person in Maury County, versus $29,859 per person across the entire state of Tennessee).[3][226]

The median household income varies significantly within the county, with the median income in Spring Hill ($90,778) being nearly twice that of Columbia ($49,284). (Note that the Spring Hill statistic includes both Maury and Williamson County parts of that city).[227][228]

The Economic Policy Institute estimated in 2018 that 99 percent of Maury County residents had incomes less than $255,385 in 2015 (the national threshold for the top 1 percent was $421,926 and the Tennessee state threshold was $332,913). The average earner in the bottom 99 percent had an income of $45,697 and the average earner in the top 1 percent of Maury County had an income of $501,397. The EPI estimated that the top 1 percent earned 10 percent of the county's total income (versus the national figure of the top 1 percent earning 21 percent of the nation's income).[231]

The poverty rate in Maury County was estimated to be 8.5 percent, which is substantially lower than the Tennessee statewide average of 13.9 percent.[3][226] The poverty rate is about five times higher in Columbia (13.9 percent) than it is Spring Hill (2.8 percent, Williamson-inclusive).[227][228]

The median sale price of homes sold is about $252,995.[232] The median value of a housing unit in Maury County was estimated by the Census Bureau as being $184,800. About 69.9 percent of housing units were owner-occupied in the 2015-2019 time period.[3]

Educational Attainment and Veteran Status

About 90.2 percent of the population of Maury County older than 25 has graduated from high school, which is somewhat higher than the state average (87.5 percent). About 23.0 percent of adults over 25 holds at least a Bachelor's degree, somewhat lower than the Tennessee state average (27.3 percent).[3][226]

The college-educated share of the population is about three times higher in Spring Hill (46.8 percent, inclusive of Williamson County parts of Spring Hill) than it is Columbia (18.8 percent). But high school graduation rates are similar (89.4 percent in Columbia versus 95.1 percent in Spring Hill).[227][228]

About 5,417 veterans are living in Maury County (about 7.3 percent of the over-18 population).[3]

Crime

Five law enforcement agencies in Maury County report crime statistics to the FBI:[233]

- Maury County Sheriff's Office[234]

- Columbia Police Department[235]

- Mount Pleasant Police Department[236]

- Spring Hill Police Department (also serves Williamson County)[237]

- Columbia State Community College[238]

| All Violent Crimes | All Property Crimes | |

|---|---|---|

| Maury County Sheriff's Office | 127 | 444 |

| Columbia Police Department | 185 | 1,235 |

| Mount Pleasant Police Department | 5 | 48 |

| Spring Hill Police Department[239] | 49 | 385 |

| Columbia State Community College | 0 | 0 |

| All Violent Crimes | Homicide | Rape | Robbery | Aggravated Assault |

All Property Crimes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maury County Sheriff's Office | 123.2 | 1.2 | 18.8 | 6.4 | 96.8 | 463 |

| Columbia Police Department | 194.6 | 2 | 23.2 | 32.8 | 136.6 | 1,227.4 |

| Mount Pleasant Police Department | 17.4 | 0 | 3 | 1.2 | 13.2 | 76.6 |

| Spring Hill Police Department[240] | 49.8 | 0.4 | 7.4 | 2.6 | 39.4 | 402.2 |

| Columbia State Community College | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Religion

According to the 2010 U.S. Religion Census, there were 190 congregations in Maury County with 38,353 adherents (defined as full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services), for an adherence rate of 474 per 1,000 residents. The adherence rate in Maury County is somewhat below the Tennessee statewide average of 555 adherents per 1,000 residents and close to the national average of 488 adherents per 1,000 residents.[241][242][243]

The 2010 U.S. Religion Census data shows 136 congregations and 24,645 adherents were identified as Evangelical Protestant; 14 congregations with 2,029 adherents identified as Black Protestant; 31 congregations with 5,864 adherents identified as Mainline Protestant; and 2 congregations with 3,900 adherents were identified as Roman Catholic. An additional 7 congregations with 1,915 adherents were identified as "Other", a category that embraces denominations such as the Jehovah's Witnesses and Latter-Day Saints, as well as non-Christian faith traditions. [244] The largest denominations by number of adherents in Maury County were: Southern Baptist (8,244), Church of Christ (7,675), United Methodist (4,166), Roman Catholic (3,900), Non-Denominational (3,149) and Latter-Day Saints (1,592).[245] There are an estimated 308 Muslims in Maury County.[246]

Since 1980, the fastest-growing denominations in Maury County in percentage terms have been the Roman Catholic Church (+954%), the Latter-Day Saints (+512%), and Assemblies of God (+299%). The denominations that gained the most adherents were the Roman Catholic Church (+3,530), the Latter-Day Saints (+1,332), and the Southern Baptists (+1,285). There has been a significant drop in the number of Cumberland Presbyterians (-279) and Methodists (-973) during this time frame. The adherence rate for Evangelical Protestantism slightly declined during this time, with Evangelicals making up about 69 percent of the county's religious adherents in 1980 and about 65 percent in 2010. The overall adherence rate for all religious traditions was the same -- 47.4 percent -- in both 1980 and 2010, but there was a significant surge in adherence in the 1980s (with the adherence rate reaching 55.2 percent in 1990) followed by a long slide in the two decades that followed.[247]

The 2010 U.S. Religion Census does not attempt to survey the non-religious. A Pew Survey in 2014 found that 14 percent of adult Tennesseans were religiously unaffiliated and 11 percent identified as "nothing in particular." It also found that, while 51 percent of adult Tennesseans reported attending church once per week or more, 24 percent seldom or never attended services. Pew found that 91 percent of adult Tennesseans expressed an "absolutely" or "fairly" certain belief in God, with 3 percent not believing in God, and the remainder expressing some degree of agnosticism.[248]

Government

County Government

County Commission

The legislative body for Maury County is the County Commission (formally, "Board of Commissioners"). The County Commission is responsible for crafting the county's budget as well as other local policies. The County Commission meets every third Monday at 6:30 p.m at the Tom Primm Meeting Room at 6 Courthouse Square, Columbia (across the street from the County Courthouse in the Hunter Matthews complex).[249]

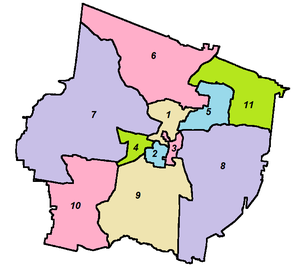

The Tennessee state constitution specifies that a county commission can have as many as 25 members, with each district having up to three members.[250] The Maury County Commission is currently composed of 22 members, with two members each from eleven districts.[251] County Commission districts are redrawn at least every ten years using data from the most recent United States Census.[252] The next round of reapportionment will occur before January 1, 2022.[253]

Commissioners serve four-year terms.[254] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

For a complete list of County Commissioners, please see the article "Maury County Commission."

County Mayor (County Executive)

The County Mayor (also referred to in the state constitution as the County Executive) is the chief executive officer of Maury County. The County Mayor is elected for a four-year term.[255] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

The current County Mayor is Andy Ogles.

For a complete list of Maury County Mayors, please see the article "Mayor of Maury County, Tennessee."

Sheriff

The Sheriff is the chief law enforcement officer of Maury County. The Sheriff is elected for a four-year term.[256] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

The current County Mayor is Bucky Rowland.

For a complete list of Maury County Sheriffs, please see the article "Sheriff of Maury County, Tennessee."

County Clerk

The County Clerk of Maury County is responsible for keeping the records of the County Commission as well as issuing various licenses and permits (including marriage licenses, alarm permits, automobile titles and license plates, and processing applications for notaries public). The County Clerk is elected for a four-year term.[257] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

The current County Clerk is Joey Allen.[258]

Trustee

The Trustee is the chief financial officer, treasurer, and banker for Maury County. The Trustee receives tax revenue for the county. The Trustee is elected for a four-year term.[259] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

The current Trustee is Randy McNeece.[260]

Register of Deeds

The Register of Deeds is the county officer responsible for recording, archiving, and making available for inspection deeds and other real estate and business documents. The Register of Deeds is elected for a four-year term.[261] The most recent election was held on August 2, 2018. The next election will occur on Thursday, August 4, 2022.

The current Register of Deeds is John Fleming.[262]

Assessor of Property

The Assessor of Property is the county officer responsible for valuing most residential and business property for tax purposes. The Assessor of Property is elected for a four-year term.[263] The most recent election was held on August 6, 2020 and the next election will be held on August 1, 2024.

The current Assessor of Property is Bobby Daniels.[264]

Road Superintendent

The Road Superintendent oversees the Maury County Highway Department. The Highway Department maintains the county's roads. The Highway Superintendent is elected for a four-year term.[265] The most recent election was held on August 6, 2020 and the next election will be held on August 1, 2024.

The current Road Superintendent is Van G. Boshers.[266]

State Government in Maury County

Representation in Tennessee General Assembly

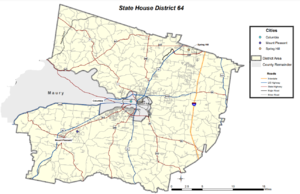

Maury County is divided between the 64th and 69th State House districts and is part of the 28th State Senate District. [268]

The 64th District is currently represented by Rep. Scott Cepicky (R).

The 69th District is currently represented by Rep. Michael Curcio (R).

The 28th Senate District is currently represented by Sen. Joey Hensley (R).

State Courts in Maury County

Maury County is in the 22nd Judicial District, along with Giles, Wayne, and Lawrence Counties.[269][270]

Circuit Court (22nd Judicial District)

The Circuit Court is a court of general jurisdiction which hears criminal and civil cases, as well as appeals from General Sessions, Juvenile Court, and municipal courts.[271][272][273]

The current Circuit Court Judges for the 22nd Judicial District (in order of seniority) are:

- Judge Stella L. Hargrove, appointed in 1998 by Gov. Don Sundquist and last elected to an eight-year term as an Independent in 2014.[274][275]

- Presiding Judge John Russell Parkes, appointed in 2014 by Gov. Bill Haslam and last elected to an eight-year term as a Republican in 2016.[276][277]

- Judge David Lee Allen, appointed in 2015 by Gov. Bill Haslam and last elected to an eight-year term as a Republican in 2016.[278][279][280]

- Judge Christopher V. Sockwell, appointed in 2018 by Gov. Bill Haslam and last elected to an eight-year term as a Republican in 2020.[281]

When sitting in Maury County, the Circuit Court holds court at the Maury County Courthouse. [282]

The Circuit Court Clerk in Maury County is Sandy McLain, who was elected as an Independent to a four-year term in 2018. The Circuit Court Clerk's office also serves the General Sessions and Juvenile Courts.[283][284]

Chancery Court (22nd Judicial District)

The Chancery Court is a court of equity with jurisdiction partly overlapping that of the Circuit Court.[285][286][287] An important duty of the Chancery Court is to handle probate matters.[288]

There are is currently no full-time chancellor in the 22nd Judicial District, so the Chancery Court powers are exercised by the Circuit Court trial judges as well as the county Clerks and Masters.[289] The Clerk and Master in Maury County is Larry Roe.[290] The Clerk and Master is appointed for a six-year term by the Circuit Court judges.[291]

Maury County General Sessions Court

The General Sessions Courts are limited jurisdiction courts created by the General Assembly.[292] In Maury County, the General Sessions Court has jurisdiction over traffic tickets, misdemeanor criminal cases (where the defendant waives the right to a grand jury indictment and jury trial), and civil cases where the amount in controversy is less than $25,000.[293][294][295] In Maury County, the General Sessions judges also have jurisdiction over juvenile cases.[296] Cases from General Sessions can be appealed to the Circuit Court.[297]

The General Sessions Court in Maury County has two parts; Part I sits in Columbia and Part II sits in Mount Pleasant.[298]

There are currently three General Sessions judges in Maury County:

- Associate Judge Bobby Sands, who was last elected as an Independent in 2014.[299][300]

- Judge (Part I) Douglas K. Chapman, who was last elected as a Republican in 2018.[301]

- Judge (Part II) J. Lee Bailey, III, who was last elected as an Independent in 2014.[302][303]

General Sessions judges serve for eight-year terms.[304][305]

Municipal Courts

The cities of Spring Hill, Columbia, and Mount Pleasant have municipal courts which enforce city ordinances and traffic offenses.[306][307]

District Attorney General (22nd Judicial District)

The District Attorney General (or District Attorney) is responsible for prosecuting criminal cases on behalf of the State of Tennessee.[308] The term of office for the District Attorney General is eight years.[309]

The current District Attorney General for the 22nd District is Brent Cooper, who was last elected as a Republican in 2014.[310]

District Public Defender (22nd Judicial District)

The District Public Defender is responsible for representing indigent defendants in criminal cases in state court.[311]

The District Public Defender is elected for an eight-year term.[312] Travis Jones was appointed in 2019 and elected to a full term in 2020.[313][314]

Federal Government in Maury County

Representation in the United States Congress

In addition to being represented by two United States Senators from Tennessee, Maury County is currently divided between the 4th and 7th United States Congressional Districts.[315]

As of 2021, the U.S. House members representing Maury County are:

- Dr. Scott DesJarlais representing the 4th Congressional District.

- Dr. Mark Green representing the 7th Congressional District.

Federal Courts

The United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee as well as the United States Bankruptcy Court for Middle Tennessee both hold court sessions at the old U.S. Courthouse (815 S. Garden Street) in Columbia, though their administrative offices are in Nashville.[316][317] Appeals from the Middle District of Tennessee go to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.[318]

Federal Agencies

The United States Postal Service maintains the following post offices in Maury County[319]:

- Columbia (417 West 7th Street; 931-388-6161)

- Culleoka (2349 Culleoka Highway; 831-987=2286)

- Hampshire (4116 Hampshire Pike; 931-285-2312)

- Mt. Pleasant (201 N. Main Street; 931-379-3285)

- Santa Fe (2581 Santa Fe Pike; 931-682-2594)

- Spring Hill (223 Town Center Parkway; 931-486-2629)

- Williamsport (3568 Williamsport Pike; 931-583-2562)

The Social Security Administration maintains an office at 1885 Shady Brook Street in Columbia.[320]

The United States Department of Agriculture maintains a service center at 803 Hatcher Lane in Columbia.[321]

The United States Department of Defense has military recruiting stations in Maury County:[322]

- Army / Navy - 800 S James M Campbell Blvd., Columbia.

- Air Force / Marine Corps - 807 Nashville Highway, Columbia.

Politics in Maury County

Parties

Interest Groups

Voting in Maury County

Election Results

For historical presidential election results, see Presidential Elections in Maury County

For historical gubernatorial election results, see Gubernatorial Elections in Maury County

For historical congressional election results, see Congressional Elections in Maury County

Public Finance

For a discussion of the Maury County budget, see the article "Maury County Budget."

Taxes

Maury County has a local option sales and use tax of 2.75 percent. This was raised from 2.25 percent by voter referendum in 2020.[323] This is in addition to the 7 percent statewide sales tax (on non-food items; a lower rate of 4 percent applies for food items) for a 9.75 combined sales tax rate.[324]

The property tax rate is currently $2.2364 per $100 of the assessed value of the taxable property (for residential property, this is 25 percent of the appraised value). For example, a home appraised value of $100,000 would pay $559 in county property tax annually (not including city tax).[325][326]

Public Debt

As of June 30, 2020, Maury County had $165 million in outstanding debt principal.[327] In December 2020, Moody's gave Maury County's 2020 bonds an Aa2 rating, calling the county's debt load "above-average but manageable." This is the same rating as Nashville-Davidson Metro but two ranks lower than neighboring Williamson County (Aaa).[328][329]

Economy and Major Businesses

Overview

Maury County produced $4.36 billion (current 2019 dollars) in goods and services in 2019, ranking 16th among Tennessee counties. Personal income was $4.26 billion, with $2.82 billion coming from net earnings (e.g. salaries, wages, and employee benefits), $939 million from current transfer receipts (e.g. Social Security and welfare payments), $869 million from retirement funds, and $504 million from dividends, interest payments or rent.

There were 54,221 paid jobs in Maury County in 2019. Of these, 40,103 are wage-earning jobs and 14,118 are proprietor jobs (i.e. self-employment). The largest sectors in Maury County by paid employment in 2019 were:

- Government (7,339 jobs, 5,704 of which were local government jobs)

- Manufacturing (7,137 jobs; note that this does not include mining or transportation)

- Retail trade (5,830 jobs)

- Health Care and Social Assistance (4,513 jobs)

- Accommodation and Food Services (4,008 jobs)

- Real Estate and Leasing (3,464 jobs)

- Administrative and support, etc. (3,270 jobs)

- Other services (3,264 jobs; those does not include professional/technical services or transportation services)

- Finance and insurance (2,942 jobs)

- Construction (2,889 jobs)

By payroll, the largest industries are:

- Manufacturing ($618 million)

- Government ($465 million)

- Health Care ($217 million)

- Finance ($163 million)

- Retail Trade ($157 million)

- Wholesale Trade ($129 million)

- Real Estate ($108 million)

Farm employment was approximately 1,553, with most of those being farm proprietors themselves; farm payroll was only $2.4 million.[331]

Maury County had a civilian workforce of 51,206 and an unemployment rate of 5.8 percent (up from 2.8 percent in November 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic; not seasonally-adjusted) in December 2020.[332] Maury County had a slightly lower unemployment rate than the State of Tennessee for most of the 2010s.[333]

According to Census Data from 2011-2015, about 15,834 Maury County residents commute to jobs outside the county and about 10,673 residents of other counties commute to Maury County places of employment. About 22,404 county residents hold jobs requiring a commute to somewhere else in Maury County. The top counties where Maury County residents commute to are Williamson (8,350), Nashville-Davidson (3,875), Marshall (905), and Rutherford (885). The top counties from which employees commute to Maury County include Williamson (2,838), Lawrence (1,775), Marshall (1,447), and Giles (804).[334]

Agriculture

In 2017 (the most recent agricultural census), there were 2,592 farm operators and 1,583 farms. Of these farms, 98 percent were family farms. The average age of a farm operator was 58.8 years. Almost all (96 percent) of the farm operators in Maury County were white, with about 23 identifying as Hispanic (of any race) and 61 African-American farm operators. About 44 percent of farm operators worked off-site (either at another farm or in a non-farm job) more than 200 days of the year. Almost all farms were operated either by full or part landowners; only 19 farms were operated by tenants. Only about 18 percent of farms in Maury County hired laborers. [335][336]

The average farm size was 144 acres with a total of 227,179 acres in farms (about 58 percent of the total land area of Maury County). The median farm size was 56 acres. For farmland, 35 percent was used as cropland, 37 percent as pasture land, and 24 percent as woodland.

The total market value of agricultural products sold was $45.6 million. The market value of agricultural products sold was split almost evenly between livestock and animal products (52 percent of sales) and crops (48 percent). Top products by value include grains and soybeans, cattle, and dairy products. Maury County ranked highly among Tennessee counties in hay production (10th), cattle and calves (6th), sheep and goats (9th), and cow milk production (6th). Horses, ponies, mules, and donkeys (the livestock often associated with Maury County's agricultural traditions) brought in only $254,000 in revenue in 2017, with Maury County placing 26th among Tennessee counties in sales. [337]

Most farms in Maury County (57 percent) had less than $5,000 in sales in 2017, and only 5 percent had sales greater than $100,000. The average farm in Maury County had $29,115 in expenses and only $28,788 in sales. Nevertheless, the average farm netted $2,370 in farm income (though nearly 2/3rds - 1,047 farm operations - operated with a net loss) and farm income added $3.75 million to Maury County's economy. Countywide farm earnings outpaced expenses due largely to non-sale farm income and government subsidies; farmers in Maury County received over $2.4 million in government payments in 2017.[338][339]

Agriculture was traditionally an important part of Maury County's economy. However, in recent years it has been a shrinking sector. In the past 50 years, the number of farms has declined significantly; though in recent decades the number of farms has slightly rebounded. Still, the total amount of farmland has continued to decrease, resulting in smaller and less-profitable farms. In 1969, there were 2,286 farms and covering 330,055 acres; this decreased to 1,506 farms over 245,681 acres in 1992 (with an average size of 163 acres). In 1992, the average net cash income from the sale of agricultural products was $3,301 (in 1992 dollars; over $6,154 in 2021 dollars).[340][341]

In addition to farming, many other jobs in Maury County are indirectly supported by agriculture. These include retail and professional jobs; for example, the Tennessee Farm Bureau and its affiliated insurance companies are based in Columbia.[342]

Manufacturing and Mining

Professional Services

Retail

Schools

Maury County Public Schools

Columbia State Community College System

Tennessee College of Applied Technology - Spring Hill

Public Libraries

Columbia Academy

Other Private Schools

Historical Institutions

Health Care

Hospitals

Health Department

Health Statistics

Arts and Culture

Local Media

Newspapers

Radio

Events

Mule Day

Mule Day is normally held in early April in Columbia. It is sponsored by the Maury County Bridle and Saddle Club.[343] A Mule Day parade, mule races, and live music are typically held.[344] A beauty pageant is also held in late February or early March to crown a young woman as Mule Day Queen.[345]

Mule Day was held regularly between 1974 and 2019. Events were cancelled in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic[346][347]

The event is a continuation of prior Mule Day celebrations during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[348]

County Fair

Sheriff's Rodeo

Spring Hill Art Walk

Parks

This list does not include city-owned parks.

Maury County Park

Chickasaw Trace Park

Hampshire Park

Jerry Erwin Park

Williams Spring Park

Yanahli Park

Stillhouse Hollow Falls State Scenic-Recreational Natural Area

Natchez Trace Parkway

Sports Clubs

The Columbia Soccer Association is a non-profit organization that sponsors recreational soccer teams for both youths and adults as well as the Columbia Arsenal FC competitive team.[349]

The Columbia American Little League baseball team is affiliated with Little League International.[350]

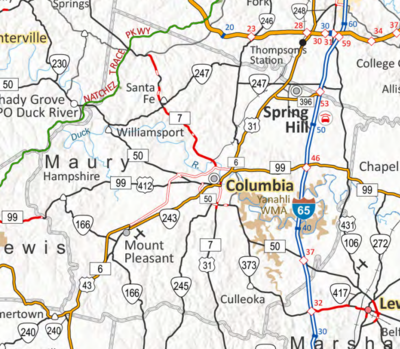

Transportation

Highways

Railroads

Airports

Communications

ZIP Codes

Telephone

Maury County is in area code 931. However, parts of Spring Hill in Williamson County are in area code 615.[351]

The following landline telephone exchanges are in use [352]:

- Culleoka - 931-987-xxxx.

- Columbia - 931-380-xxxx, 931-381-xxxx, 931-388-xxxx, 931-490-xxxx, 931-540-xxxx, 931-840-xxxx.

- Hampshire - 931-285-xxxx.

- Mount Pleasant - 931-379-xxxx.

- Santa Fe - 931-659-xxxx.

- Spring Hill (Maury County side only) - 931-486-xxxx, 931-487-xxxx, 931-489-xxxx.

- Williamsport - 931-583-xxxx.

Internet

Spectrum and Columbia Power & Water Systems provide Internet services in Columbia.

Notable People from Maury County

Politics

- President James K. Polk spent his boyhood and early business and political career in Columbia.

Military

- Leonidas Polk, a second-cousin of James K. Polk, Episcopal bishop, and Confederate general during the Civil War.

- Fran McKee, the first woman to serve as a line officer in the United States Navy.

Professional Sports

- Professional football player Shaquille Olajuwon Mason is from Columbia.

References and Footnotes

- ↑ Tenn. Code § 4-1-203 (2016).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wikipedia contributors. "Maury County, Tennessee." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 20 Jan. 2021. Web. 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 "QuickFacts: Maury County, Tennessee." U.S. Census Bureau, Undated. Web. 22 Jan. 2021..

- ↑ "Maury." Dictionary.com. Undated. Web. 23 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 http://sites.rootsweb.com/~tnmaury/history.htm Thomas, Frank D. "Maury County, Tennessee History." RootsWeb Project, 12 July 1998, Web. 23 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Robbins, D.P. Century Review: 1805-1905, Maury County, Tennessee. Columbia, Board of Mayor and Aldermen, 1905, p. 12. Web (hathitrust.org). 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Lightfoot, Marise. "Maury County." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Turner, William Bruce. History of Maury County, Tennessee. Nashville, Parthenon Press, 1955, pp. 12 -13. Web (hathitrust.org). 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ "An Act to reduce Williamson county to constitutional limits and to form a new county on the south and southwest of the same." Acts Passed at the First Session of the Seventh General Assembly of the State of Tennessee. Knoxville, William Moore, 1808, ch. 94, pp. 149-154. Online through Vanderbilt Library. 22 Jan. 2021. Also available online at UT CTAS Website.

- ↑ Many sources say November 24, 1807; see for example the plaque on the County Courthouse or Greenlaw, R. Douglass. "Outline History of Maury County." Tennessee Historical Magazine. vol. 3, no. 3., April 1935. p. 145. JSTOR. 29 Jan. 2021. This probably refers to the date the bill (passed by the General Assembly on November 16) creating Maury County was signed by Gov. John Sevier.

- ↑ Act of 16 Nov. 1807, cited supra, at p. 151.

- ↑ | "Abram Maury", Williamson County Historical Society, Undated. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ | "Broken Treaties." Tennessee State Museum. Undated. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ Turner, supra at 15.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 U.S. Department of State. Abstract of the Fifth Census of the United States, 1830. Washington, The Globe Office, 1832 Web (hathitrust.org). 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 U.S. Department of State, Compendium of the enumeration of inhabitants and statistics of the United States. Washington, Thomas Allen, 1841. Web (hathitrust.org). 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ Turner, supra at 16.

- ↑ Robbins, cited supra, at 14.

- ↑ Turner, supra, at 16.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "James K. Polk." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Jan. 2021. Web. 23 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "President James K. Polk Home & Museum." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 Dec. 2020. Web. 23 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kennedy, Joseph C.G. Population of the United States in 1860. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1864. Web (census.gov). 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Mann, Lina. "The Enslaved Household of President James K. Polk." 3 Jan. 2020. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ "Maury County Timeline." Undated. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ See the 1860 Census Slave Schedules. "United States Census Slave Schedules." FamilySearch Wiki. 9 Dec 2020. Web. 23 Jan 2021.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "Rippavilla Plantation." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 9 Oct. 2020. Web. 23 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Blais, Matt. "Spring Hill hopes to attract Rippavilla tourism with truth about its history of slavery." Spring Hill Home Page. 19 Jan. 2018. Web. 22 Jan. 2021

- ↑ Turner, supra, at 367.

- ↑ Duncan, Bob. "Manumission - The Struggle for an Uncertain Freedom." Maury County Second Century Review. Columbia, Maury County Archives, 2007, pp. 114-116.

- ↑ It is acknowledged that this term is anachronistic and may be offensive; it is the term used in the original Census documents.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Walker, Francis A. (Superintendent of the Census). Ninth Census - Volume I: The Statistics of the Population of the United States. Washington,. Government Printing Office, 1872. Web (census.gov). 31 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Adams, J.Q. (Secretary of State). Census for 1820. Washington,. Gales & Seaton, 1821. Web (census.gov). 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ DeBow, J.D.B. The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850. Washington, Robert Armstrong, 1853. Web (census.gov). 22 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Turner, cited supra, at pp. 207-209. Note that a full-strength company would have had about 100 men, but this number may have varied over time.

- ↑ Turner, supra at 209.

- ↑ Turner, cited supra, at 224.

- ↑ Turner, cited supra, at pp. 231-33.

- ↑ Turner, cited supra at 139, 217.

- ↑ Logsdon, David R. "Earl Van Dorn." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018, Web. 26 Jan. 2021

- ↑ Watkins, Sam R. and McAllister, Ruth Hill Fulton (editor). Company Aytch, or a Side Show of the Big Show: A Memoir of the Civil War. Nashville, Turner Publishing Company, 2011.

- ↑ Hargett, Tre (Secretary of State). Tennessee Blue Book 2019-2020. Nashville, Tennessee Secretary of State, 2020. pp. 608=09.

- ↑ Carey, Bill. Runaways, Coffles, and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee. Nashville, Clearbrook Press, 2018. pp. 232-36.

- ↑ McKenzie, Robert Tracy. "Reconstruction." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 27 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Turner, cited supra, at pp. 354-58

- ↑ Wetherington, Mark V. "Ku Klux Klan." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 27 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ O'Brien, Gail Williams. The Color of the Law: Race, Violence, and Justice in the Post-World War II South. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, pp. 116-118. HeinOnline through Vanderbilt University library. 1 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ African American Heritage Society of Maury County, “Freedman's (sic) Bureau Exhibit on Display at Fairview Park Recreational Center.” The Daily Herald, The Daily Herald, 23 Feb. 2013, Web. 31 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ Robbins, cited supra, at 160.

- ↑ Lightwood, cited supra.

- ↑ Coppedge, Needham, and Christian, John. "A History of Phosphates in Maury County", in Turner, cited supra, at pp. 331-38.

- ↑ Keys, Juanita. "Phosphate Mining and Industry." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 1 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Duncan, Bob. "When Phosphate was King; Mt. Pleasant in 1912." Maury County Second Century Review. Columbia, Maury County Archives, 2007. pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Lightwood, cited supra.

- ↑ Coppedge and Christian, cited supra.

- ↑ "Colored" plus 2 "Indians."

- ↑ Walker, Francis A. and Seaton, Chas. (Superintendents of the Census). Statistics of the Population of the United States at the Tenth Census (June 1, 1880). Washington, Government Printing Office, 1883. Web (census.gov). 31 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ "Colored" plus 2 "Indians."

- ↑ Porter, Robert P. and Wright, Carroll D. (Superintendents of the Census). Report on Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Part I. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1895. Web. (census. gov). 31 Jan. 2021.

- ↑ "Negro" plus 1 "Indian."